Confessions

As human beings, our entire life is full of errors and shortcomings. We wrong people, and they wrong us. Sometimes intentionally, sometimes unintentionally. We apologize, and we forgive.

In my close to forty years, I’ve done quite a few things I’m ashamed of. In fact, I liken myself to being one bad thing away from starring as the villain in a Disney movie. Shame may not be the right word, as according to the shame researcher Brene Brown, shame is indicative of the person, not what they did. But still, I have done things that are worth apologizing for.

I am a planner by nature, and making lists is one of my hobbies. It would make perfect sense for someone like me to map out my plotted revenge, then joyfully cross it off once complete like Santa Clause. However, despite the organized, vengeful side of me, most of the wrongdoings that, on occasion, keep me up at night were rash decisions, fueled by emotions and pain. Or they were mistakes made from ignorance, the naivety of not knowing, or worse, not taking action when I did understand. My wrongdoings have not been plotted out. I have not become that villain yet.

As a creative, I’m always looking for ways to express myself to the world. Confessing my sins is no exception. One day in my early thirties, after having been sober for a year and graduating with my bachelor’s, the self-induced burdens I carried became too heavy to bear. I was obsessing about one particularly vile thing I’d done, wishing for a way to apologize to the person, without letting them know I was the one who had done it. I considered sending them an anonymous letter but thought they may hire a PI to fingerprint it, thus tracing it back to me.

I then began analyzing not only the thing I’d done but why I felt so bad about it. And how I could feel as bad as I did, wanting to send an apology letter, yet remain anonymous at the same time. Did I need the forgiveness of the person I’d wronged, or was I looking for someone else’s?

From previous experience of reading self-help blogs, and from the insistence of past therapists, I was well aware of letter-writing as an act of healing. The act of writing a letter to someone, whether that be to yourself (past or present version) or to someone else, regardless of what actually becomes of the letter, can have a healing effect when dealing with past traumas, shame, and pain. I have written such letters, later ripping them up without sharing them with the intended receiver. And I still have many other letters like that to write, the deep end of the ocean style letters. The type of letters I don’t want anyone else to ever actually read.

The idea of writing down my anonymous confessions would come to fruit many months later, after having moved unexpectedly across the country for my husband’s job and a fresh start. We left New Orleans and moved to the Seattle area, without having ever visited it. The agonizingly long road trip in a moving truck with our two cats gave me more than enough time to think about my need to confess, and how to make it happen.

As I further pondered my desire to confess, yet stay anonymous, I was able to determine that the apology I wished to make was more to myself than to the person I’d wronged. If our case was brought to the court of law, I could argue my way around what I’d done and how yes, it had been reckless and wrong but was also a retribution for what was happening to me at that moment. I wanted to apologize to those I’d wronged, and needed to make it right with myself and the universe. I say the universe rather than God, as I relate more towards Agnostic Atheism than the Christianity I was raised in. However, it may not be the universe I want to include in this equation. This third component is something greater than myself and the other party involved, a higher power, something I can only describe as my moral compass, but on a grander scale.

I’ve come to understand the act of confession, and who it involves as being triadic. This was something I’d recognized in the past but had yet to fully grasp until reading the chapter, “Making Confessions,” by George Jensen. Written history reminds us that the act of confessing is about more than the listener and confessor, but also about this third party. For Augustine, I believe this third to be God. Montaigne, on the other hand, may view this third to be his sense of vulnerability and desire of relatability with his peers or those he deems to be his jury. Or, as said during class discussion, perhaps Montaigne’s third is his reflection on the philosophy of the Stoics and other authors before his time. Each individual may view this third to be different from another’s, whether consciously or unconsciously. Jensen says in this chapter, “As members of the Oxford Group and Alcoholics Anonymous explain it, we share our searching moral inventory with another human being, who is a representative of the divine other.” This divine other for me is what I’ve deemed as my moral compass.

My moral compass gets rusty at times, but I am still fully aware of what I consider to be right versus wrong. It is the basis for which I judge myself and others, although I don’t particularly like to be the one judging. The mistakes I made were wrong, and I had known it at the time. I came to the conclusion that the apology I wanted to make was meant for me as well because I was sorry for letting myself down. I was sorry for hurting someone else, for wanting to hurt them, and for holding onto the guilt that gnawed away at my insides over the years.

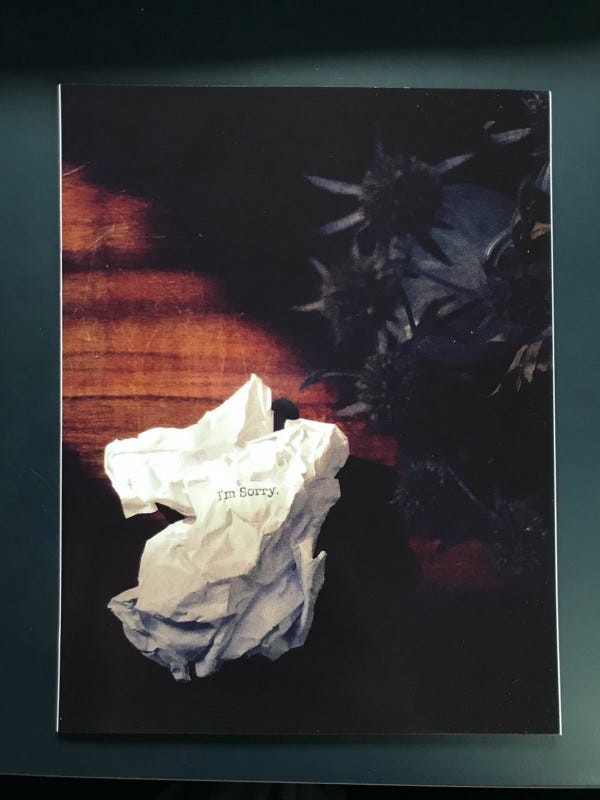

Ultimately, my desire to apologize led me to create a project that would grant me the freedom to apologize, with anonymity, and also let others participate if they so desired. After hours contemplating the best way to put this idea into fruition, I finally decided on the idea of one submitting their apologies anonymously by way of postcard or by completing an electronic form on the website I’d created. I called it the Forgiveness Manifesto.

I spent months perfecting the image to match the vision I had, while also working to make the instructional copy clear and concise. Once satisfied, I printed hundreds of these postcards and began giving them to friends and family. I would also leave them at local coffee shops and pin them up to the community events board in different businesses. During a multi layover flight, I left them in airport terminals and in the seatback pockets of planes.

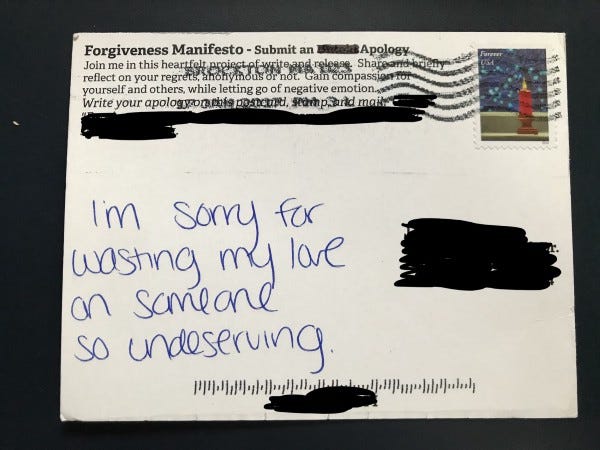

My instructions to the submitter were simple: Submit an apology. Join me in this heartfelt project of write and release. Share and briefly reflect on your regrets, anonymous or not. Gain compassion for yourself and others, while letting go of negative emotion. Write your apology on this postcard, stamp, and mail.

I didn’t push the project as hard as I should’ve, but in the year it was active before moving back across the country, I’d received several submissions. Some were the postcards being sent back to me, while others were through the online submission form located on my website.

The project eventually fizzled out as I began working on other things, and has yet to become the intended coffee-style book. However, I still consider it to be a project worthy of starting back up at some point in my life. When I think of myself or others who may have a sense of remorse that they have been unable to quell, I wonder if participating in this project could bring them some sense of solace. I think of my sister, awaiting her prison sentence for charges resulting from her drug addiction. Could the act of an anonymous confession act as a bridge through which vulnerability and acceptance can flow, allowing her self-forgiveness and healing while on the road to recovery?

I am reminded of the act of confessing in relation to religion, particularly Catholicism, where one confesses anonymously to a priest. I consider my project to be different from this as I am asking the confessor to share their confession with the world, rather than with one person who keeps your secrets in exchange for penance.

Perhaps as the writers we’ve studied in class have done, the act of sharing a confession helps with self-acceptance, leading to forgiveness while gaining the power to acknowledge our perceived wrongdoings without allowing them to paralyze us from continuing to fully live our lives.

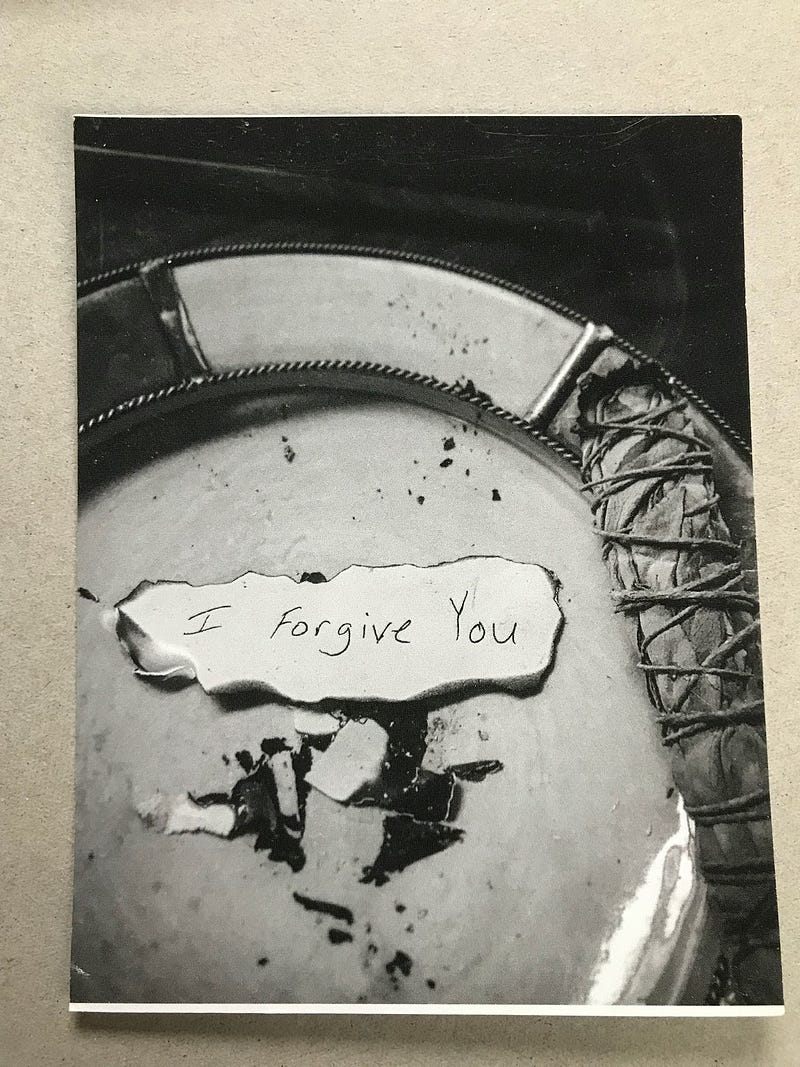

During the time spent working on this project, my idea shifted to not only apologizing, but I began to wonder if it would be helpful for others to declare their forgiveness as well. If a confession is ultimately sharing something one has done that may be perceived as wrong, bad, shameful, or embarrassing, then what could acknowledging forgiveness do?

I think the answer to this question is similar to the answer of what confession can do. Ultimately we are here to connect with each other and to feel a sense of community and belonging. Like every other human being on this planet, we will each go through life making mistakes that hurt ourselves and others while simultaneously being hurt by the wrongdoings of others. Whether we are acknowledging our own shortcomings or those of someone else and how they’ve hurt us, we are putting ourselves out into the world to ultimately heal from the pain we’ve experienced, and to know that we are not alone. Everyone goes through life with varying situations and events, but we are in this experience of life together. Our existence as humans is collective.

Writing about our experiences helps to strengthen the human connection shared by everyone on this planet. We put ourselves out into the world, easing the loneliness felt as writers while letting others know they are not alone on this tremulous journey called life. Confession and forgiveness are part of our existence just as physical touch and emotional warmth are. The more we share our experiences, the more connected and understood we feel. And the more accepted we are, the better our human experience.